Focusing on efficiency and ignoring effectiveness is the root cause of most software project failures.

Focusing on efficiency and ignoring effectiveness is the root cause of most software project failures.

Effectiveness is producing the intended or expected result. Efficiency is the ability to accomplish a job with a minimum expenditure of time and effort.

Effective software projects deliver code that the end users need; efficient projects deliver that code with a minimum number of resources and time.

Sometimes, we become so obsessed with things we can measure, i.e. project end date, kLOC, that we somehow forget what we were building in the first place. When you’re up to your hips in alligators, it’s hard to remember you were there to drain the swamp.

Sometimes, we become so obsessed with things we can measure, i.e. project end date, kLOC, that we somehow forget what we were building in the first place. When you’re up to your hips in alligators, it’s hard to remember you were there to drain the swamp.

Efficiency only matters if you are being effective.

After 50 years, the top three end-user complaints about software are:

- It took too long

- It cost too much

- It doesn’t do what we need

Salaries are the biggest cost of most software projects, hence if it takes too long then it will cost too much, so we can reduce the complaints to:

- It took too long

- It doesn’t do what we need

The first issue is a complaint about our efficiency and the second is a complaint about our effectiveness. Let’s make sure that we have common definitions of these two issues before continuing to look at the interplay between efficiency and effectiveness.

Are We There Yet?

Are you late if you miss the project end date?

That depends on your point of view; consider a well specified project (i.e. good requirements) with a good work breakdown structure that is estimated

by competent architects to take a competent team of 10 developers at least 15 months to build. Let’s consider 5 scenarios where this is true except as stated below:

Under which circumstances is a project late?

A. Senior management gives the team 6 months to build the software.

B. Senior management assigns a team of 5 competent developers instead of 10.

C. Senior management assigns a team of 10 untrained developers

D. You have the correct team, but, each developer needs to spend 20-35% of their time maintaining code on another legacy system

E. The project is staffed as expected

Here are the above scenarios in a table:

|

#

|

Team

|

Resource

Commitment

|

Months Given

|

Result

|

|

A

|

10 competent developers

|

100%

|

6

|

Unrealistic estimate

|

|

B

|

5

competent developers

|

100%

|

15

|

Under staffed

|

|

C

|

10 untrained developers

|

100%

|

15

|

Untrained staff

|

|

D

|

10 competent developers

|

65-80%

|

15

|

Team under committed

|

|

E

|

10 competent developers

|

100%

|

15

|

Late

|

Only the last project (E) is late because the estimation of the end date was consistent with the project resources available.

Other well known variations which are not late when the end date is missed:

- Project end date is a SWAG or management declared

- Project has poor requirements

- You tell the end-user 10 months when the estimate is 15 months.

If any of the conditions of project E are missing then you have a problem in estimation. You may still be late, but not based on the project end date computed with bad assumptions

Of course, being late may be acceptable if you deliver a subset of the expected system.

It Doesn’t Work

“It doesn’t do what we need” is a failure to deliver what the end user needs. How so we figure out what the end user needs?

The requirements for a system come from a variety of sources:

- End-users

- Sales and marketing (includes competitors)

- Product management

- Engineering

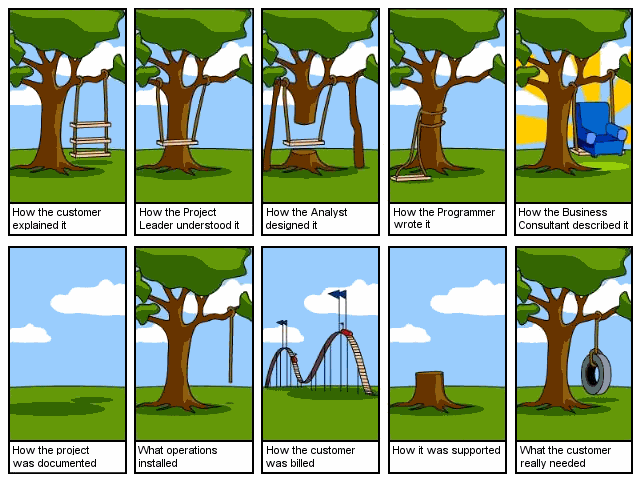

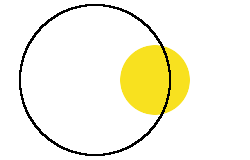

These initial requirements will rarely be consistent with each other. In fact, each of these constituents will have a different impression of the requirements. You would expect the raw requirements to be contradictory in places. The beliefs are like the 4 circles to the left, and the intersection of their beliefs would be the black area.

The different sources of requirements do not agree because:

- Everyone has a different point of view

- Everyone has a different set of beliefs about what is being built

- Everyone has a different capability of articulating their needs

- Product managers have varying abilities to synthesize consistent requirements

It is the job of product management to synthesize the different viewpoints into a single set of consistent requirements. If engineering starts before

requirements are consistent then you will end up with many fire-fighting meetings and lose time.

Many projects start before the requirements are consistent enough. We hope the initial requirements are a subset of what is required.

In practice, we have missed requirements and included requirements that are not needed (see bottom of post, data from Capers Jones)

The yellow circle represents what we have captured, the black circle represents the real requirements.

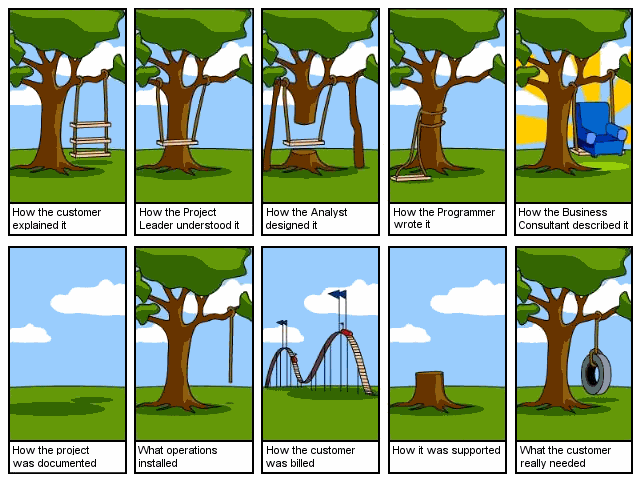

We rarely have consistent requirements when we start a project, that is why there are different forms of the following cartoon lying around on the Internet.

If you don’t do all the following:

- Interview all stakeholders for requirements

- Get end-users to articulate their real needs by product management

- Synthesize consistent requirements

Then you will fail to build the correct software. So if you skip any of this work then you are guaranteed to get the response, “It doesn’t do what we need”.

Effectiveness vs. Efficiency

So, let’s repeat our user complaints:

- It took too long

- It doesn’t do what we need

It’s possible to deliver the correct software late.

It’s impossible to deliver on-time if the software doesn’t work

Focusing on effectiveness is more important than efficiency if a software project is to be delivered successfully.

Ineffectiveness Comes from Poor Requirements

Most organizations don’t test the validity or completeness of their requirements before starting a software project.

The requirements get translated into a project plan and then the project manager will attempt to execute the project plan. The project plan becomes the bible and everyone marches to it. As long as tasks are completed on time everyone assumes that you are effective, i.e. doing the right thing.

That is until virtually all the tasks are jammed at 95% complete and the project is nowhere near completion.

At some point someone will notice something and say, “I don’t think this feature should work this way”. This will provoke discussions between developers, QA, and product management on correct program behavior. This will spark a series of fire-fighting meetings to resolve the inconsistency, issue a defect, and fix the problem. All of the extra meetings will start causing tasks on the project plan to slip.

We discussed the root causes of fire-fighting in a previous blog entry.

When fire-fighting starts productivity will grind to a halt. Developers will lose productivity because they will end up being pulled into the endless meetings. At this point the schedule starts slipping and we become focused on the project plan and deadline. Scope gets reduced to help make the project deadline; unfortunately, we tend to throw effectiveness out the window at this point.

With any luck the project and product manager can find a way to reduce scope enough to declare victory after missing the original deadline.

The interesting thing here is that the project failed before it started. The real cause of the failure would be the inconsistent requirements.But, in the chaos of fire-fighting and endless meetings, no one will remember that the requirements were the root cause of

The interesting thing here is that the project failed before it started. The real cause of the failure would be the inconsistent requirements.But, in the chaos of fire-fighting and endless meetings, no one will remember that the requirements were the root cause of

the problem.

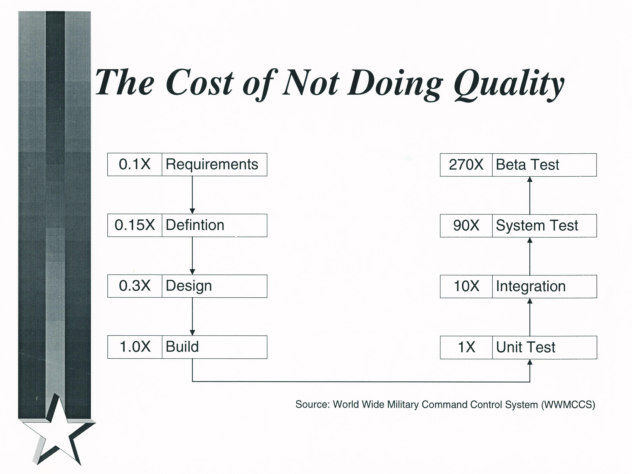

What is the cost of poor requirements? Fortunately, WWMCCS has an answer. As a military organization they must tracks everything in a detailed fashion and perform root cause analysis for each defect (diagram).

This drawing shows what we know to be true.

The longer a requirement problem takes to discover, the harder and more expensive it is to fix! A requirement that would take 1 hour to fix will take 900 hours to fix if it slips to system testing.

Conclusion

It is much more

important to focus on effectiveness during a project than efficiency. When it becomes clear that you will not make the project end date, you need to stay

focused on building the correct software.

Are you tired of the cycle of:

- Collecting inconsistent requirements?

- Building a project plan based on the inconsistent requirements?

- Estimating projects and having senior management disbelieve it?

- Focusing on the project end date and not on end user needs?

- Fire-fighting over inconsistent requirements?

- Losing developer productivity from endless meetings?

- Not only miss the end date but also not deliver what the end-users need?

The fact that organizations go through this cycle over and over while expecting successful projects is insanity – real world Dilbert cartoons.

How many times are you going to rinse and repeat this process until you try something different? If you want to break this cycle, then you need to start collecting consistent requirements.

How many times are you going to rinse and repeat this process until you try something different? If you want to break this cycle, then you need to start collecting consistent requirements.

Think about the impact to your career of the following scenarios:

- You miss the deadline but build a subset of what the end-user needs

- You miss the deadline and don’t have what the end-user needs

You can at least declare some kind of victory in scenario 1 and your resume will not take a big hit. It’s pretty hard to make up for scenario 2 no matter how you slice it.

Alternatively, you can save yourself wasted time by making sure the requirements are consistent before you start development. Inconsistent requirements will lead to fire-fighting later in the project.

As a developer, when you are handed the requirements the team should make a point of

looking for inconsistent requirements.

The entire team should go through the requirements and look for inconsistencies and force product management to fix them before you start developing.

It may sound like a waste of time but it will push the problem of poor requirements back into product management and save you from being in endless meetings. Cultivating patience on holding out for good requirements will lower your blood pressure and help you to sleep at night.

Of course, once you get good requirements then you should hold out for proper project estimates 🙂

| Want to see other sacred cows get tipped?Check out:

|

|

|

Moo? |

Courtesy of Capers Jones via LinkedIn on 6/22

Customers themselves are often not sure of their requirements.

For a large system of about 10,000 function points, here is what might be seen for the requirements.

This is from a paper on requirements problems – send an email to capers.jones3@gmail.com if you want a copy.

Requirements specification pages = 2,500

Requirements words = 1,125,000

Requirements diagrams = 300

Specific user requirements = 7,407

Missing requirements = 1,050

Incorrect requirements = 875

Superfluous requirements = 375

Toxic harmful requirements = 18

Initial requirements completeness = < 60%

Total requirements creep = 2,687 function points

Deferred requirements to meet schedule = 1,522

Complete and accurate requirements are possible < 1000 function points. Above that errors and missing requirements are endemic.

VN:F [1.9.22_1171]

Rating: 0.0/5 (0 votes cast)

VN:F [1.9.22_1171]

Connecting with your customers and delivering value depends on understanding your customer’s requirements and selling the correct product or solution that solves your customer’s problems.

Connecting with your customers and delivering value depends on understanding your customer’s requirements and selling the correct product or solution that solves your customer’s problems. The more that product customization or creation is required, the more it is important understand the customer’s actual problem. The more time required to build and implement a solution means will not only lead to a failed sale but also to a more disappointed customer and a loss of future revenue.

The more that product customization or creation is required, the more it is important understand the customer’s actual problem. The more time required to build and implement a solution means will not only lead to a failed sale but also to a more disappointed customer and a loss of future revenue. Time pressures to make a sale put us under pressure and this stress leads to making quick decisions about whether a product or solution can be sold to a customer. We listen to the customer but interpret everything he says according to the products and solutions that we have.

Time pressures to make a sale put us under pressure and this stress leads to making quick decisions about whether a product or solution can be sold to a customer. We listen to the customer but interpret everything he says according to the products and solutions that we have. We hear the word car and we think that we know what the customer means. The order-taker sales person will spring into action and sell what he thinks the customer needs. Behind the word car is an implied usage and unless you can ferret out the meaning that the customer has in mind, you are unlikely to sell the correct solution.

We hear the word car and we think that we know what the customer means. The order-taker sales person will spring into action and sell what he thinks the customer needs. Behind the word car is an implied usage and unless you can ferret out the meaning that the customer has in mind, you are unlikely to sell the correct solution.For products that require customization, the sale will get transferred to professional services that will dig deeper into the customer’s requirements. At this point you discover that the needs of the customer cannot be met. This leads to sales people putting pressure on professional services and product management to ‘find a solution’, after all, losing the sale is not an option.

Sometimes heroic actions by the product management, professional services, and software development teams lead to a successful implementation, but usually not until there has been severe pain at the customer and midnight oil burned in your company. You can eventually be successful but that customer will never buy from you again.

Sometimes heroic actions by the product management, professional services, and software development teams lead to a successful implementation, but usually not until there has been severe pain at the customer and midnight oil burned in your company. You can eventually be successful but that customer will never buy from you again. Selling the correct solution to the customer requires that you understand the customer’s problem before you sell the solution.

Selling the correct solution to the customer requires that you understand the customer’s problem before you sell the solution.

You can see a couple, but only few people can see the entire forest by just looking at the code. For the rest of us, diagrams are the way to see the forest, and UML is the standard for diagrams.

You can see a couple, but only few people can see the entire forest by just looking at the code. For the rest of us, diagrams are the way to see the forest, and UML is the standard for diagrams. Contrast that with software where UML diagrams are rarely produced, or if they are produced, they are produced as an after thought. The irony is that the people pushing to build the architecture quickly say that there is no time to make diagrams, but they are the first people to complain when the architecture sucks. UML is key to planning (see

Contrast that with software where UML diagrams are rarely produced, or if they are produced, they are produced as an after thought. The irony is that the people pushing to build the architecture quickly say that there is no time to make diagrams, but they are the first people to complain when the architecture sucks. UML is key to planning (see  Yet this is where all the architecture is. Good architecture makes all the difference in medium and large systems. Architecture is the glue that holds the software components in place and defines communication through the structure. If you don’t plan the layers and modules of the system then you will continually be making compromises later on.

Yet this is where all the architecture is. Good architecture makes all the difference in medium and large systems. Architecture is the glue that holds the software components in place and defines communication through the structure. If you don’t plan the layers and modules of the system then you will continually be making compromises later on. Good diagrams, in particular UML, allow you to abstract away all the low level details of an implementation and let you focus on planning the architecture. This higher level planning leads to better architecture and therefore better extensibility and maintainability of software.

Good diagrams, in particular UML, allow you to abstract away all the low level details of an implementation and let you focus on planning the architecture. This higher level planning leads to better architecture and therefore better extensibility and maintainability of software. These analysis level UML diagrams will help you to identify gaps in the requirements before moving to design. This way you can send your BAs and product managers back to collect missing requirements when you identify missing elements before you get too far down the road.

These analysis level UML diagrams will help you to identify gaps in the requirements before moving to design. This way you can send your BAs and product managers back to collect missing requirements when you identify missing elements before you get too far down the road.

How many times are you going to rinse and repeat this process until you try something different? If you want to break this cycle, then you need to start collecting consistent requirements.

How many times are you going to rinse and repeat this process until you try something different? If you want to break this cycle, then you need to start collecting consistent requirements.